This Thread Is Dedicated To Discuss On History And Philosophy Of Lord Buddha Gautama Buddha |

|

|---|---|

A statue of the Buddha from Sarnath, 4th century CE

|

|

| Born | c. 563 BCE [1] Lumbini (present-day in Nepal)[1] or possibly elsewhere |

| Died | c. 483 BCE (aged 80) or 411 and 400 BCE Kushinagar (present-day in Uttar Pradesh, India) |

| Known for | Founder of Buddhism |

| Predecessor | Kassapa Buddha |

| Successor | Maitreya Buddha |

|

Gautama Buddha, also known as Siddhrtha Gautama[note 1], Shakyamuni,[note 2], or simply the Buddha, was a sage[2] on whose teachings Buddhism was founded.[3] A native of the ancient Shakya republic in the Himalayan foothills,[4][note 3] Gautama Buddha taught primarily in northeastern India.

Buddha means "awakened one" or "the enlightened one." "Buddha" is also used as a title for the first awakened being in an era. In most Buddhist traditions, Siddhartha Gautama is regarded as the Supreme Buddha (Pali sammsambuddha, Sanskrit samyaksabuddha) of our age. [note 4]

Gautama taught a Middle Way between sensual indulgence and the severe asceticism found in the Sramana (renunciation) movement [11] common in his region. He later taught throughout regions of eastern India such as Magadha and Koala.[12][13]

The times of Gautama's birth and death are uncertain: most historians in the early 20th century dated his lifetime as circa 563 BCE to 483 BCE,[14] but more recent opinion dates his death to between 486 and 483 BCE or, according to some, between 411 and 400 BCE.[15] [note 5] However, at a symposium on this question held in 1988,[14] the majority of those who presented definite opinions gave dates within 20 years either side of 400 BCE for the Buddha's death. These alternative chronologies, however, have not yet been accepted by all other historians.[16][17]

Gautama is the primary figure in Buddhism, and accounts of his life, discourses, and monastic rules are believed by Buddhists to have been summarized after his death and memorized by his followers. Various collections of teachings attributed to him were passed down by oral tradition, and first committed to writing about 400 years later.

The primary sources for the life of Siddhrtha Gautama are a variety of different, and sometimes conflicting, traditional biographies. These include the Buddhacarita, Lalitavistara Stra, Mahvastu, and the Nidnakath.[18] Of these, the Buddhacarita[19][20] is the earliest full biography, an epic poem written by the poet Avaghoa, and dating around the beginning of the 2nd century CE.[18] The Lalitavistara Stra is the next oldest biography, a Mahyna/Sarvstivda biography dating to the 3rd century CE.[21] The Mahvastu from the Mahsghika Lokottaravda tradition is another major biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE.[21] The Dharmaguptaka biography of the Buddha is the most exhaustive, and is entitled the Abhinikramaa Stra,[22] and various Chinese translations of this date between the 3rd and 6th century CE. Lastly, the Nidnakath is from the Theravda tradition in Sri Lanka, was composed in the 5th century CE by Buddhaghoa.[23]

From canonical sources, the Jtakas, the Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14), and the Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123) include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full biographies. The Jtakas retell previous lives of Gautama as a bodhisattva, and the first collection of these can be dated among the earliest Buddhist texts.[24] The Mahpadna Sutta and Achariyabhuta Sutta both recount miraculous events surrounding Gautama's birth, such as the bodhisattva's descent from Tuita Heaven into his mother's womb.

Traditional biographies of Gautama generally include numerous miracles, omens, and supernatural events. The character of the Buddha in these traditional biographies is often that of a fully transcendent (Skt. lokottara) and perfected being who is unencumbered by the mundane world. In the Mahvastu, over the course of many lives, Gautama is said to have developed supramundane abilities including: a painless birth conceived without intercourse; no need for sleep, food, medicine, or bathing, although engaging in such "in conformity with the world"; omniscience, and the ability to "suppress karma".[25] Nevertheless, some of the more ordinary details of his life have been gathered from these traditional sources. In modern times there has been an attempt to form a secular understanding of Siddhrtha Gautama's life by omitting the traditional supernatural elements of his early biographies.

Andrew Skilton writes that the Buddha was never historically regarded by Buddhist traditions as being merely human:[26]

It is important to stress that, despite modern Theravada teachings to the contrary (often a sop to skeptical Western pupils), he was never seen as being merely human. For instance, he is often described as having the thirty-two major and eighty minor marks or signs of a mahpurua, "superman"; the Buddha himself denied that he was either a man or a god; and in the Mahparinibbna Sutta he states that he could live for an aeon were he asked to do so.

The ancient Indians were generally unconcerned with chronologies, being more focused on philosophy. Buddhist texts reflect this tendency, providing a clearer picture of what Gautama may have taught than of the dates of the events in his life. These texts contain descriptions of the culture and daily life of ancient India which can be corroborated from the Jain scriptures, and make the Buddha's time the earliest period in Indian history for which significant accounts exist.[27][full citation needed] British author Karen Armstrong writes that although there is very little information that can be considered historically sound, we can be reasonably confident that Siddhrtha Gautama did exist as a historical figure.[28][dubious - discuss] Michael Carrithers goes a bit further by stating that the most general outline of "birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death" must be true.[29][unreliable source?]

Most scholars regard Kapilavastu, present-day Nepal, to be the birthplace of the Buddha.[5][6][note 7] Other possibilities are Lumbini, present-day Nepal [note 8] Kapileswara, Odisha, present-day India; [note 9] and Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, present-day India.[note 10]

According to the most traditional biography,[which?] Buddha was born in a royal Hindu family[30] to King uddhodana, the leader of Shakya clan, whose capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha's lifetime. Gautama was the family name. His mother, Queen Maha Maya (Mydev) and Suddhodana's wife, was a Koliyan princess. Legend has it that, on the night Siddhartha was conceived, Queen Maya dreamt that a white elephant with six white tusks entered her right side,[web 5] and ten months later Siddhartha was born. As was the Shakya tradition, when his mother Queen Maya became pregnant, she left Kapilvastu for her father's kingdom to give birth. However, her son is said to have been born on the way, at Lumbini, in a garden beneath a sal tree.

The day of the Buddha's birth is widely celebrated in Theravada countries as Vesak.[31] Buddha's birth anniversary holiday is called "Buddha Poornima" in India as Buddha is believed to have been born on a full moon day. Various sources hold that the Buddha's mother died at his birth, a few days or seven days later. The infant was given the name Siddhartha (Pli: Siddhattha), meaning "he who achieves his aim". During the birth celebrations, the hermit seer Asita journeyed from his mountain abode and announced that the child would either become a great king (chakravartin) or a great holy man.[32] By traditional account,[which?] this occurred after Siddhartha placed his feet in Asita's hair and Asita examined the birthmarks. Suddhodana held a naming ceremony on the fifth day, and invited eight brahmin scholars to read the future. All gave a dual prediction that the baby would either become a great king or a great holy man.[32] Kaundinya (Pali: Kondaa), the youngest, and later to be the first arahant other than the Buddha, was reputed to be the only one who unequivocally predicted that Siddhartha would become a Buddha.[33]

While later tradition and legend characterized uddhodana as a hereditary monarch, the descendant of the Solar Dynasty of Ikvku (Pli: Okkka), many scholars think that uddhodana was the elected chief of a tribal confederacy.

Early texts suggest that Gautama was not familiar with the dominant religious teachings of his time until he left on his religious quest, which is said to have been motivated by existential concern for the human condition.[34] At the time, many small city-states existed in Ancient India, called Janapadas. Republics and chiefdoms with diffused political power and limited social stratification, were not uncommon amongst them, and were referred to as gana-sanghas.[35] The Buddha's community does not seem to have had a caste system. It was not a monarchy, and seems to have been structured either as an oligarchy, or as a form of republic.[36] The more egalitarian gana-sangha form of government, as a political alternative to the strongly hierarchical kingdoms, may have influenced the development of the Shramana-type Jain and Buddhist sanghas, where monarchies tended toward Vedic Brahmanism.[37]

Siddhartha was born in a royal Hindu family.[30] He was brought up by his mother's younger sister, Maha Pajapati.[38] By tradition, he is said to have been destined by birth to the life of a prince, and had three palaces (for seasonal occupation) built for him. Although more recent scholarship doubts this status, his father, said to be King uddhodana, wishing for his son to be a great king, is said to have shielded him from religious teachings and from knowledge of human suffering.

When he reached the age of 16, his father reputedly arranged his marriage to a cousin of the same age named Yaodhar (Pli: Yasodhar). According to the traditional account,[which?] she gave birth to a son, named Rhula. Siddhartha is said to have spent 29 years as a prince in Kapilavastu. Although his father ensured that Siddhartha was provided with everything he could want or need, Buddhist scriptures say that the future Buddha felt that material wealth was not life's ultimate goal.[38]

At the age of 29, the popular biography[which?] continues, Siddhartha left his palace to meet his subjects. Despite his father's efforts to hide from him the sick, aged and suffering, Siddhartha was said to have seen an old man. When his charioteer Channa explained to him that all people grew old, the prince went on further trips beyond the palace. On these he encountered a diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an ascetic. These depressed him, and he initially strove to overcome ageing, sickness, and death by living the life of an ascetic.[39]

Accompanied by Channa and riding his horse Kanthaka, Gautama quit his palace for the life of a mendicant. It's said that, "the horse's hooves were muffled by the gods"[40] to prevent guards from knowing of his departure.

Gautama initially went to Rajagaha and began his ascetic life by begging for alms in the street. After King Bimbisara's men recognised Siddhartha and the king learned of his quest, Bimbisara offered Siddhartha the throne. Siddhartha rejected the offer, but promised to visit his kingdom of Magadha first, upon attaining enlightenment.

He left Rajagaha and practised under two hermit teachers of yogic meditation.[41][42][43] After mastering the teachings of Alara Kalama (Skr. ra Klma), he was asked by Kalama to succeed him. However, Gautama felt unsatisfied by the practise, and moved on to become a student of yoga with Udaka Ramaputta (Skr. Udraka Rmaputra).[44] With him he achieved high levels of meditative consciousness, and was again asked to succeed his teacher. But, once more, he was not satisfied, and again moved on.[45]

Siddhartha and a group of five companions led by Kaundinya are then said to have set out to take their austerities even further. They tried to find enlightenment through deprivation of worldly goods, including food, practising self-mortification. After nearly starving himself to death by restricting his food intake to around a leaf or nut per day, he collapsed in a river while bathing and almost drowned. Siddhartha began to reconsider his path. Then, he remembered a moment in childhood in which he had been watching his father start the season's plowing. He attained a concentrated and focused state that was blissful and refreshing, the jhna.

According to the early Buddhist texts,[web 6] after realizing that meditative jhana was the right path to awakening, but that extreme asceticism didn't work, Gautama discovered what Buddhists call the Middle Way[web 6]"a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification.[web 6] In a famous incident, after becoming starved and weakened, he is said to have accepted milk and rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata.[web 7] Such was his emaciated appearance that she wrongly believed him to be a spirit that had granted her a wish.[web 7]

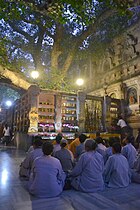

Following this incident, Gautama was famously seated under a pipal tree"now known as the Bodhi tree"in Bodh Gaya, India, when he vowed never to arise until he had found the truth.[46] Kaundinya and four other companions, believing that he had abandoned his search and become undisciplined, left. After a reputed 49 days of meditation, at the age of 35, he is said to have attained Enlightenment.[46][47] According to some traditions, this occurred in approximately the fifth lunar month, while, according to others, it was in the twelfth month. From that time, Gautama was known to his followers as the Buddha or "Awakened One" ("Buddha" is also sometimes translated as "The Enlightened One").

According to Buddhism, at the time of his awakening he realized complete insight into the cause of suffering, and the steps necessary to eliminate it. These discoveries became known as the "Four Noble Truths",[47] which are at the heart of Buddhist teaching. Through mastery of these truths, a state of supreme liberation, or Nirvana, is believed to be possible for any being. The Buddha described Nirvna as the perfect peace of a mind that's free from ignorance, greed, hatred and other afflictive states,[47] or "defilements" (kilesas). Nirvana is also regarded as the "end of the world", in that no personal identity or boundaries of the mind remain. In such a state, a being is said to possess the Ten Characteristics, belonging to every Buddha.

According to a story in the ycana Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya VI.1) " a scripture found in the Pli and other canons " immediately after his awakening, the Buddha debated whether or not he should teach the Dharma to others. He was concerned that humans were so overpowered by ignorance, greed and hatred that they could never recognise the path, which is subtle, deep and hard to grasp. However, in the story, Brahm Sahampati convinced him, arguing that at least some will understand it. The Buddha relented, and agreed to teach.

After his awakening, the Buddha met two merchants, named Tapussa and Bhallika, who became his first lay disciples. They were apparently each given hairs from his head, which are now claimed to be enshrined as relics in the Shwe Dagon Temple in Rangoon, Burma. The Buddha intended to visit Asita, and his former teachers, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta, to explain his findings, but they had already died.

He then travelled to the Deer Park near Vras (Benares) in northern India, where he set in motion what Buddhists call the Wheel of Dharma by delivering his first sermon to the five companions with whom he had sought enlightenment. Together with him, they formed the first sagha: the company of Buddhist monks.

All five become arahants, and within the first two months, with the conversion of Yasa and fifty four of his friends, the number of such arahants is said to have grown to 60. The conversion of three brothers named Kassapa followed, with their reputed 200, 300 and 500 disciples, respectively. This swelled the sangha to more than 1,000.

For the remaining 45 years of his life, the Buddha is said to have traveled in the Gangetic Plain, in what is now Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and southern Nepal, teaching a diverse range of people: from nobles to outcaste street sweepers, murderers such as Angulimala, and cannibals such as Alavaka. From the outset, Buddhism was equally open to all races and classes, and had no caste structure, as was the rule for most Hindus in the-then society. Although the Buddha's language remains unknown, it's likely that he taught in one or more of a variety of closely related Middle Indo-Aryan dialects, of which Pali may be a standardization.

The sangha traveled through the subcontinent, expounding the dharma. This continued throughout the year, except during the four months of the vassana rainy season when ascetics of all religions rarely traveled. One reason was that it was more difficult to do so without causing harm to animal life. At this time of year, the sangha would retreat to monasteries, public parks or forests, where people would come to them.

The first vassana was spent at Varanasi when the sangha was formed. After this, the Buddha kept a promise to travel to Rajagaha, capital of Magadha, to visit King Bimbisara. During this visit, Sariputta and Maudgalyayana were converted by Assaji, one of the first five disciples, after which they were to become the Buddha's two foremost followers. The Buddha spent the next three seasons at Veluvana Bamboo Grove monastery in Rajagaha, capital of Magadha.

Upon hearing of his son's awakening, Suddhodana sent, over a period, ten delegations to ask him to return to Kapilavastu. On the first nine occasions, the delegates failed to deliver the message, and instead joined the sangha to become arahants. The tenth delegation, led by Kaludayi, a childhood friend of Gautama's (who also became an arahant), however, delivered the message.

Now two years after his awakening, the Buddha agreed to return, and made a two-month journey by foot to Kapilavastu, teaching the dharma as he went. At his return, the royal palace prepared a midday meal, but the sangha was making an alms round in Kapilavastu. Hearing this, Suddhodana approached his son, the Buddha, saying:

"Ours is the warrior lineage of Mahamassata, and not a single warrior has gone seeking alms"

The Buddha is said to have replied:

"That is not the custom of your royal lineage. But it is the custom of my Buddha lineage. Several thousands of Buddhas have gone by seeking alms"

Buddhist texts say that Suddhodana invited the sangha into the palace for the meal, followed by a dharma talk. After this he is said to have become a sotapanna. During the visit, many members of the royal family joined the sangha. The Buddha's cousins Ananda and Anuruddha became two of his five chief disciples. At the age of seven, his son Rahula also joined, and became one of his ten chief disciples. His half-brother Nanda also joined and became an arahant.

Of the Buddha's disciples, Sariputta, Maudgalyayana, Mahakasyapa, Ananda and Anuruddha are believed to have been the five closest to him. His ten foremost disciples were reputedly completed by the quintet of Upali, Subhoti, Rahula, Mahakaccana and Punna.

In the fifth vassana, the Buddha was staying at Mahavana near Vesali when he heard news of the impending death of his father. He is said to have gone to Suddhodana and taught the dharma, after which his father became an arahant.

The king's death and cremation was to inspire the creation of an order of nuns. Buddhist texts record that the Buddha was reluctant to ordain women. His foster mother Maha Pajapati, for example, approached him, asking to join the sangha, but he refused. Maha Pajapati, however, was so intent on the path of awakening that she led a group of royal Sakyan and Koliyan ladies, which followed the sangha on a long journey to Rajagaha. In time, after Ananda championed their cause, the Buddha is said to have reconsidered and, five years after the formation of the sangha, agreed to the ordination of women as nuns. He reasoned that males and females had an equal capacity for awakening. But he gave women additional rules (Vinaya) to follow.

According to colorful legends, even during the Buddha's life the sangha was not free of dissent and discord. For example, Devadatta, a cousin of Gautama who became a monk but not an arahant, more than once tried to kill him.

Initially, Devadatta is alleged to have often tried to undermine the Buddha. In one instance, according to stories, Devadatta even asked the Buddha to stand aside and let him lead the sangha. When this failed, he is accused of having three times tried to kill his teacher. The first attempt is said to have involved him hiring a group of archers to shoot the awakened one. But, upon meeting the Buddha, they laid down their bows and instead became followers. A second attempt is said to have involved Devadatta rolling a boulder down a hill. But this hit another rock and splintered, only grazing the Buddha's foot. In the third attempt, Devadatta is said to have got an elephant drunk and set it loose. This ruse also failed.

After his lack of success at homicide, Devadatta is said to have tried to create a schism in the sangha, by proposing extra restrictions on the Vinaya. When the Buddha again prevailed, Devadatta started a breakaway order. At first, he managed to convert some of the bhikkhus, but Sariputta and Maudgalyayana are said to have expounded the dharma so effectively that they were won back.

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Pali canon, at the age of 80, the Buddha announced that he would soon reach Parinirvana, or the final deathless state, and abandon his earthly body. After this, the Buddha ate his last meal, which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant nanda to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with his passing and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as it provided the last meal for a Buddha.[web 8] Dr Mettanando and Von Hinber argue that the Buddha died of mesenteric infarction, a symptom of old age, rather than food poisoning.[48][note 11]

The precise contents of the Buddha's final meal are not clear, due to variant scriptural traditions and ambiguity over the translation of certain significant terms; the Theravada tradition generally believes that the Buddha was offered some kind of pork, while the Mahayana tradition believes that the Buddha consumed some sort of truffle or other mushroom. These may reflect the different traditional views on Buddhist vegetarianism and the precepts for monks and nuns.

Ananda protested the Buddha's decision to enter Parinirvana in the abandoned jungles of Kuinra (present-day Kushinagar, India) of the Malla kingdom. The Buddha, however, is said to have reminded Ananda how Kushinara was a land once ruled by a righteous wheel-turning king that resounded with joy:

44. Kusavati, Ananda, resounded unceasingly day and night with ten sounds"the trumpeting of elephants, the neighing of horses, the rattling of chariots, the beating of drums and tabours, music and song, cheers, the clapping of hands, and cries of "Eat, drink, and be merry!"

The Buddha then asked all the attendant Bhikkhus to clarify any doubts or questions they had. They had none. According to Buddhist scriptures, he then finally entered Parinirvana. The Buddha's final words are reported to have been: "All composite things (Sakhra) are perishable. Strive for your own liberation with diligence" (Pali: 'vayadhamm sakhr appamdena sampdeth'). His body was cremated and the relics were placed in monuments or stupas, some of which are believed to have survived until the present. For example, The Temple of the Tooth or "Dalada Maligawa" in Sri Lanka is the place where what some believe to be the relic of the right tooth of Buddha is kept at present.

According to the Pli historical chronicles of Sri Lanka, the Dpavasa and Mahvasa, the coronation of Emperor Aoka (Pli: Asoka) is 218 years after the death of Buddha. According to two textual records in Chinese (- and -), the coronation of Emperor Aoka is 116 years after the death of Buddha. Therefore, the time of Buddha's passing is either 486 BCE according to Theravda record or 383 BCE according to Mahayana record. However, the actual date traditionally accepted as the date of the Buddha's death in Theravda countries is 544 or 545 BCE, because the reign of Emperor Aoka was traditionally reckoned to be about 60 years earlier than current estimates. In Burmese Buddhist tradition, the date of the Buddha's death is 13 May 544 BCE,[49] whereas in Thai tradition it is 11 March 545 BCE.[50]

At his death, the Buddha is famously believed to have told his disciples to follow no leader. Mahakasyapa was chosen by the sangha to be the chairman of the First Buddhist Council, with the two chief disciples Maudgalyayana and Sariputta having died before the Buddha.

While in Buddha's days he was addressed by the very respected titles Buddha, Shkyamuni, Shkyasimha, Bhante and Bho, he was known after his parinirvana as Arihant, Bhagav/Bhagavat/Bhagwn, Mahvira,[51] Jina/Jinendra, Sstr, Sugata, and most popularly in scriptures as Tathgata.

After his death, the Buddha was cremated and the ashes divided among his disciples. According to the PBS series Secrets of the Dead, an urn containing these was discovered in a stupa at Piprahwa near Birdpur [historical British variant as Birdpore], a Buddhist sacred structure in the Basti district of Uttar Pradesh in India by amateur archaeologist William Claxton Peppe in 1898. They were given to the King of Siam (Thailand) a couple of years later, where they still reside.

An extensive and colorful physical description of the Buddha has been laid down in scriptures. A kshatriya by birth, he had military training in his upbringing, and by Shakyan tradition was required to pass tests to demonstrate his worthiness as a warrior in order to marry. He had a strong enough body to be noticed by one of the kings and was asked to join his army as a general. He is also believed by Buddhists to have "the 32 Signs of the Great Man".

The Brahmin Sonadanda described him as "handsome, good-looking, and pleasing to the eye, with a most beautiful complexion. He has a godlike form and countenance, he is by no means unattractive."(D,I:115).

"It is wonderful, truly marvellous, how serene is the good Gotama's appearance, how clear and radiant his complexion, just as the golden jujube in autumn is clear and radiant, just as a palm-tree fruit just loosened from the stalk is clear and radiant, just as an adornment of red gold wrought in a crucible by a skilled goldsmith, deftly beaten and laid on a yellow-cloth shines, blazes and glitters, even so, the good Gotama's senses are calmed, his complexion is clear and radiant." (A,I:181)

A disciple named Vakkali, who later became an arahant, was so obsessed by Buddha's physical presence that the Buddha is said to have felt impelled to tell him to desist, and to have reminded him that he should know the Buddha through the Dhamma and not through physical appearances.

Although there are no extant representations of the Buddha in human form until around the 1st century CE (see Buddhist art), descriptions of the physical characteristics of fully enlightened buddhas are attributed to the Buddha in the Digha Nikaya's Lakkhaa Sutta (D,I:142).[52] In addition, the Buddha's physical appearance is described by Yasodhara to their son Rahula upon the Buddha's first post-Enlightenment return to his former princely palace in the non-canonical Pali devotional hymn, Narasha Gth ("The Lion of Men").[web 10]

Among the 32 main characteristics it is mentioned that Buddha has blue eyes.[53]

The nine virtues of the Buddha appear throughout the Tipitaka.[54] Recollection of the nine virtues of the Buddha is a common Buddhist devotional practice, it is also one of the 40 Buddhist meditation subjects.

Some scholars believe that some portions of the Pali Canon and the gamas contain the actual substance of the historical teachings (and possibly even the words) of the Buddha.[55][56] Some scholars believe the Pali Canon and the Agamas pre-date the Mahyna stras.[57] The scriptural works of Early Buddhism precede the Mahayana works chronologically, and are treated by many Western scholars as the main credible source for information regarding the actual historical teachings of Gautama Buddha. However, some scholars do not think that the texts report on historical events.[58][dubious - discuss][59][60]

Hajime Nakamura writes that there is nothing in the traditional Buddhist texts that can be clearly attributed to Gautama as a historical figure:[61]

[I]n the Buddhist texts there is no word that can be traced with unquestionable authority to Gautama kyamuni as a historical personage, although there must be some sayings or phrases derived from him.

Some of the fundamentals of the teachings attributed to Gautama Buddha are:

However, in some Mahayana schools, these points have come to be regarded as more or less subsidiary. There is disagreement amongst various schools of Buddhism over more complex aspects of what the Buddha is believed to have taught, and also over some of the disciplinary rules for monks.

According to tradition, the Buddha emphasized ethics and correct understanding. He questioned everyday notions of divinity and salvation. He stated that there is no intermediary between mankind and the divine; distant gods are subjected to karma themselves in decaying heavens; and the Buddha is only a guide and teacher for beings who must tread the path of Nirva (Pli: Nibbna) themselves to attain the spiritual awakening called bodhi and understand reality. The Buddhist system of insight and meditation practice is not claimed to have been divinely revealed, but to spring from an understanding of the true nature of the mind, which must be discovered by treading the path guided by the Buddha's teachings.

In Hinduism, Gautama is regarded as one of the ten avatars of God Vishnu.[note 6]

The Buddha is also regarded as a prophet by the Ahmadiyya Muslims[62][63][64] and a Manifestation of God in the Bah' faith.[65] Some early Chinese Taoist-Buddhists thought the Buddha to be a reincarnation of Lao Tzu.[66]

The Christian Saint Josaphat is based on the life of the Buddha. The name comes from the Sanskrit Bodhisatva via Arabic Bdhasaf and Georgian Iodasaph.[67] The only story in which St. Josaphat appears, Barlaam and Josaphat, is based on the life of the Buddha.[68] Josaphat was included in earlier editions of the Roman Martyrology (feast day 27 November) " though not in the Roman Missal " and in the Eastern Orthodox Church liturgical calendar (26 August).

Edited by RoseFairy - 10 years agoIn the sixth century before the Christian era, religion was forgotten in India. The lofty teachings of the Vedas were thrown into the background. There was much priestcraft everywhere. The insincere priests traded on religion. They duped the people in a variety of ways and amassed wealth for themselves. They were quite irreligious. In the name of religion, people followed in the footsteps of the cruel priests and performed meaningless rituals. They killed innocent dumb animals and did various sacrifices. The country was in dire need of a reformer of Buddha's type. At such a critical period, when there were cruelty, degeneration and unrighteousness everywhere, reformer Buddha was born to put down priestcraft and animal sacrifices, to save the people and disseminate the message of equality, unity and cosmic love everywhere.

Buddha's father was Suddhodana, king of the Sakhyas. Buddha's mother was named Maya. Buddha was born in B.C. 560 and died at the age of eighty in B.C. 480. The place of his birth was a grove known as Lumbini, near the city of Kapilavastu, at the foot of Mount Palpa in the Himalayan ranges within Nepal. This small city Kapilavastu stood on the bank of the little river Rohini, some hundred miles north-east of the city of Varnasi. As the time drew nigh for Buddha to enter the world, the gods themselves prepared the way before him with celestial portents and signs. Flowers bloomed and gentle rains fell, although out of season; heavenly music was heard, delicious scents filled the air. The body of the child bore at birth the thirty-two auspicious marks (Mahavyanjana) which indicated his future greatness, besides secondary marks (Anuvyanjana) in large numbers. Maya died seven days after her son's birth. The child was brought up by Maya's sister Mahaprajapati, who became its foster-mother.

On the birth of the child, Siddhartha, the astrologers predicted to its father Suddhodana: "The child, on attaining manhood, would become either a universal monarch (Chakravarti), or abandoning house and home, would assume the robe of a monk and become a Buddha, a perfectly enlightened soul, for the salvation of mankind". Then the king said: "What shall my son see to make him retire from the world ?". The astrologer replied: "Four signs". "What four ?" asked the king. "A decrepit old man, a diseased man, a dead man and a monk - these four will make the prince retire from the world" replied the astrologers.

Suddhodana thought that he might lose his precious son and tried his level best to make him attached to earthly objects. He surrounded him with all kinds of luxury and indulgence, in order to retain his attachment for pleasures of the senses and prevent him front undertaking a vow of solitariness and poverty. He got him married and put him in a walled place with gardens, fountains, palaces, music, dances, etc. Countless charming young ladies attended on Siddhartha to make him cheerful and happy. In particular, the king wanted to keep away from Siddhartha the 'four signs' which would move him to enter into the ascetic life. "From this time on" said the king, "let no such persons be allowed to come near my son. It will never do for my son to become a Buddha. What I would wish to see is, my son exercising sovereign rule and authority over the four great continents and the two thousand attendant isles, and walking through the heavens surrounded by a retinue thirty-six leagues in circumference". And when he had so spoken, he placed guards for quarter of a league, in each of the four directions, in order that none of the four kinds of men might come within sight of his son.

Buddha's original name was Siddhartha. It meant one who had accomplished his aim. Gautama was Siddhartha's family name. Siddhartha was known all over the world as Buddha, the Enlightened. He was also known by the name of Sakhya Muni, which meant an ascetic of the Sakhya tribe.

Siddhartha spent his boyhood at Kapilavastu and its vicinity. He was married at the age of sixteen. His wife's name was Yasodhara. Siddhartha had a son named Rahula. At the age of twenty-nine, Siddhartha Gautama suddenly abandoned his home to devote himself entirely to spiritual pursuits and Yogic practices. A mere accident turned him to the path of renunciation. One day he managed, somehow or the other, to get out of the walled enclosure of the palace and roamed about in the town along with his servant Channa to see how the people were getting on. The sight of a decrepit old man, a sick man, a corpse and a monk finally induced Siddhartha to renounce the world. He felt that he also would become a prey to old age, disease and death. Also, he noticed the serenity and the dynamic personality of the monk. Let me go beyond the miseries of this Samsara (worldly life) by renouncing this world of miseries and sorrows. This mundane life, with all its luxuries and comforts, is absolutely worthless. I also am subject to decay and am not free from the effect of old age. Worldly happiness is transitory".

Gautama left for ever his home, wealth, dominion, power, father, wife and the only child. He shaved his head and put on yellow robes. He marched towards Rajgriha, the capital of the kingdom of Magadha. There were many caves in the neighbouring hills. Many hermits lived in those caves. Siddhartha took Alamo Kalamo, a hermit, as his first teacher. He was not satisfied with his instructions. He left him and sought the help of another recluse named Uddako Ramputto for spiritual instructions. At last he determined to undertake Yogic practices. He practiced severe Tapas (austerities) and Pranayama (practice of breath control) for six years. He determined to attain the supreme peace by practicing self-mortification. He abstained almost entirely from taking food. He did not find much progress by adopting this method. He was reduced to a skeleton. He became exceedingly weak.

At that moment, some dancing girls were passing that way singing joyfully as they played on their guitar. Buddha heard their song and found real help in it. The song the girls sang had no real deep meaning for them, but for Buddha it was a message full of profound spiritual significance. It was a spiritual pick-me-up to take him out of his despair and infuse power, strength and courage. The song was:

"Fair goes the dancing when the Sitar is tuned,

Tune us the Sitar neither low nor high,

And we will dance away the hearts of men.

The string overstretched breaks, the music dies,

The string overslack is dumb and the music dies,

Tune us the Sitar neither low nor high."

Buddha realized then that he should not go to extremes in torturing the body by starvation and that he should adopt the golden mean or the happy medium or the middle path by avoiding extremes. Then he began to eat food in moderation. He gave up the earlier extreme practices and took to the middle path.

Once Buddha was in a dejected mood as he did not succeed in his Yogic practices. He knew not where to go and what to do. A village girl noticed his sorrowful face. She approached him and said to him in a polite manner: "Revered sir, may I bring some food for you ? It seems you are very hungry". Gautama looked at her and said, "What is your name, my dear sister ?". The maiden answered, "Venerable sir, my name is Sujata". Gautama said, "Sujata, I am very hungry. Can you really appease my hunger ?"

The innocent Sujata did not understand Gautama. Gautama was spiritually hungry. He was thirsting to attain supreme peace and Self-realization. He wanted spiritual food. Sujata placed some food before Gautama and entreated him to take it. Gautama smiled and said, "Beloved Sujata, I am highly pleased with your kind and benevolent nature. Can this food appease my hunger ?". Sujata replied, "Yes sir, it will appease your hunger. Kindly take it now". Gautama began to eat the food underneath the shadow of a large tree, thenceforth to be called as the great 'Bo-tree' or the tree of wisdom. Gautama sat in a meditative mood underneath the tree from early morning to sunset, with a fiery determination and an iron resolve: "Let me die. Let my body perish. Let my flesh dry up. I will not get up from this seat till I get full illumination". He plunged himself into deep meditation. At night he entered into deep Samadhi (superconscious state) underneath that sacred Bo-tree (Pipal tree or ficus religiosa). He was tempted by Maya in a variety of ways, but he stood adamant. He did not yield to Maya's allurements and temptations. He came out victorious with full illumination. He attained Nirvana (liberation). His face shone with divine splendour and effulgence. He got up from his seat and danced in divine ecstasy for seven consecutive days and nights around the sacred Bo-tree. Then he came to the normal plane of consciousness. His heart was filled with profound mercy and compassion. He wanted to share what he had with humanity. He traveled all over India and preached his doctrine and gospel. He became a saviour, deliverer and redeemer.

Buddha gave out the experiences of his Samadhi: "I thus behold my mind released from the defilement of earthly existence, released from the defilement of sensual pleasures, released from the defilement of heresy, released from the defilement of ignorance."

In the emancipated state arose the knowledge: "I am emancipated, rebirth is extinct, the religious walk is accomplished, what had to be done is done, and there is no need for the present existence. I have overcome all foes; I am all-wise; I am free from stains in every way; I have left everything and have obtained emancipation by the destruction of desire. Myself having gained knowledge, whom should I call my Master ? I have no teacher; no one is equal to me. I am the holy one in this world; I am the highest teacher. I alone am the absolute omniscient one (Sambuddho). I have gained coolness by the extinction of all passion and have obtained Nirvana. To found the kingdom of law (Dharmo) I go to the city of Varnasi. I will beat the drum of immortality in the darkness of this world".

Lord Buddha then walked on to Varnasi. He entered the 'deer-park' one evening. He gave his discourse there and preached his doctrine. He preached to all without exception, men and women, the high and the low, the ignorant and the learned - all alike. All his first disciples were laymen and two of the very first were women. The first convert was a rich young man named Yasa. The next were Yasa's father, mother and wife. Those were his lay disciples.

Buddha argued and debated with his old disciples who had deserted him when he was in the Uruvila forest. He brought them round by his powerful arguments and persuasive powers. Kondanno, an aged hermit, was converted first. The others also soon accepted the doctrine of Lord Buddha. Buddha made sixty disciples and sent them in different directions to preach his doctrine.

Buddha told his disciples not to enquire into the origin of the world, into the existence and nature of God. He said to them that such investigations were practically useless and likely to distract their minds.

The number of Buddha's followers gradually increased. Nobles, Brahmins and many wealthy men became his disciples. Buddha paid no attention to caste. The poor and the outcastes were admitted to his order. Those who wanted to become full members of his order were obliged to become monks and to observe strict rules of conduct. Buddha had many lay disciples also. Those lay members had to provide for the wants of the monks.

In the forest of Uruvila, there were three brothers - all very famous monks and philosophers. They had many learned disciples. They were honoured by kings and potentates. Lord Buddha went to Uruvila and lived with those three monks. He converted those three reputed monks, which caused a great sensation all over the country.

Lord Buddha and his disciples walked on towards Rajgriha, the capital of Magadha. Bimbisara, the king, who was attended upon by 120,000 Brahmins and householders, welcomed Buddha and his followers with great devotion. He heard the sermon of Lord Buddha and at once became his disciple. 110,000 of the Brahmins and householders became full members of Lord Buddha's order and the remaining 10,000 became lay adherents. Buddha's followers were treated with contempt when they went to beg their daily food. Bimbisara made Buddha a present of Veluvanam - a bamboo-grove, one of the royal pleasure-gardens near his capital. Lord Buddha spent many rainy seasons there with his followers.

Every Buddhist monk takes a vow, when he puts on the yellow robe, to abstain from killing any living being. Therefore, a stay in one place during the rainy season becomes necessary. Even now, the Paramahamsa Sannyasins (the highest class of renunciates) of Sankara's order stay in one place for four months during the rainy season (Chaturmas). It is impossible to move about in the rainy season without killing countless small insects, which the combined influence of moisture and the hot sun at the season brings into existence.

Lord Buddha received from his father a message asking him to visit his native place, so that he might see him once more before he died. Buddha accepted his invitation gladly and started for Kapilavastu. He stayed in a forest outside the city. His father and relatives came to see him, but they were not pleased with their ascetic Gautama. They left the place after a short time. They did not make any arrangement for his and his followers' daily food. After all, they were worldly people. Buddha went to the city and begged his food from door to door. This news reached the ears of his father. He tried to stop Gautama from begging. Gautama said: "O king, I am a mendicant - I am a monk. It is my duty to get alms from door to door. This is the duty of the Order. Why do you stop this ? The food that is obtained from alms is very pure". His father did not pay any attention to the words of Gautama. He snatched the bowl from his hand and took him to his palace. All came to pay Buddha their respects, but his wife Yasodhara did not come. She said, "He himself will come to me, if I am of any value in his eyes". She was a very chaste lady endowed with Viveka (discrimination), Vairagya (dispassion) and other virtuous qualities. From the day she lost her husband she gave up all her luxuries. She took very simple food once daily and slept on a mat. She led a life of severe austerities. Gautama heard all this. He was very much moved. He went at once to see her. She prostrated at his feet. She caught hold of his feet and burst into tears. Buddha established an order of female ascetics. Yasodhara became the first of the Buddhistic nuns.

Yasodhara pointed out the passing Buddha to her son through a window and said, "O Rahula! That monk is your father. Go to him and ask for your birthright. Tell him boldly, 'I am your son. Give me my heritage'". Rahula at once went up to Buddha and said, "Dear father, give me my heritage". Buddha was taking his food then. He did not give any reply. The boy repeatedly asked for his heritage. Buddha went to the forest. The boy also silently followed him to the forest. Buddha said to one of his disciples, "I give this boy the precious spiritual wealth I acquired under the sacred Bo-tree. I make him the heir to that wealth". Rahula was initiated into the order of monks. When this news reached the ears of Buddha's father, he was very much grieved because after losing his son, he now lost his grandson also.

Buddha performed some miracles. A savage serpent of great magical power sent forth fire against Buddha. Buddha turned his own body into fire and sent forth flames against the serpent. Once a tree bent down one of its branches in order to help Buddha when he wanted to come up out of the water of a tank. One day five hundred pieces of firewood split by themselves at Buddha's command. Buddha created five hundred vessels with fire burning in them for the Jatilas to warm themselves on a winter night. When there was flood, he caused the water to recede and then he walked over the water.

Ananda, one of Buddha's cousins, was one of the principal early disciples of Buddha and was a most devoted friend and disciple of Buddha. He was devoted to Buddha with a special fervour in a simple childlike way and served him as his personal attendant till the end of his life. He was very popular. he was a very sweet man with pleasant ways. He had no intellectual attainments, but he was a man of great sincerity and loving nature. Devadatta, one of Ananda's brothers, was also in the Order. Devadatta became Buddha's greatest rival and tried hard to oust Buddha and occupy the place himself. A barber named Upali and a countryman called Anuruddha were admitted into the Order. Upali became a distinguished leader of his Order. Anuruddha became a Buddhistic philosopher of vast erudition.

Buddha went to Sravasti, the capital of the kingdom of Kosala. Here a wealthy merchant gave him for residence an extensive and beautiful forest. Buddha spent many rainy seasons there and delivered several grand discourses. Thus Lord Buddha preached his doctrine for over forty-five years traveling from place to place.

Buddha died of an illness brought on by some error in diet. He became ill through eating Sukara-maddavam, prepared for him by a lady adherent named Cundo. The commentator explains the word as meaning 'hog's flesh'. Subadhara Bhikshu thinks it means something which wild boars are fond of and says that it has something of the nature of a truffle. Dr. Hoey says that it is not boar's flesh but Sukarakanda or hog's root, a bulbous root found chiefly in the jungle and which Hindus eat with great joy. It is a Phalahar that is eaten on days of fasting.

Buddha said to Ananda, "Go Ananda, prepare for me, between twin Sal trees, a couch with the head northward. I am exhausted and would like to lie down". A wonderful scene followed. The twin Sal trees burst into full bloom although it was not the blossoming season. Those flowers fell on the body of Buddha out of reverence. Divine coral tree flowers and divine sandalwood powders fell from above on Buddha's body out of reverence.

Lord Buddha said, "Come now, dear monks. I bid you farewell. Compounds are subject to dissolution. Prosper ye through diligence and work out your salvation".

The spirit of Ahimsa (non-violence) was ever present with Gautama from his very childhood. One day, his cousin Devadatta shot a bird. The poor creature was hurt and fell to the ground. Gautama ran forward, picked it up and refused to hand it over to his cousin. The quarrel was taken up before the Rajaguru who, however, decided in favour of Gautama to the great humiliation of Devadatta.

In his wanderings, Gautama one day saw a herd of goats and sheep winding their way through a narrow valley. Now and then the herdsman cried and ran forward and backward to keep the members of the fold from going astray. Among the vast flock Gautama saw a little lamb, toiling behind, wounded in one part of the body and made lame by a blow of the herdsman. Gautama's heart was touched and he took it up in his arms and carried it saying, "It is better to relieve the suffering of an innocent being than to sit on the rocks of Olympus or in solitary caves and watch unconcerned the sorrows and sufferings of humanity". Then, turning to the herdsman he said, "Whither are you going, my friend, with this huge flock so great a hurry ?". "To the king's palace" said the herdsman, "We are sent to fetch goats and sheep for sacrifice which our master - the king - will start tonight in propitiation of the gods." Hearing this, Gautama followed the herdsman, carrying the lamb in his arms. When they entered the city, word was circulated that a holy hermit had brought the sacrifices ordered by the king. As Gautama passed through the streets, people came out to see the gracious and saintly figure of the youth clad in the yellow robes of a Sadhu (renunciate) and all were struck with wonder and awe at his noble mien and his sweet expression. The king was also informed of the coming of the holy man to the sacrifice. When the ceremonies commenced in the presence of the king, there was brought a goat ready to be killed and offered to the gods. There it stood with its legs tied up and the high priest ready with a big bloodthirsty knife in his hand to cut the dumb animal's throat. In that cruel and tragic moment, when the life of the poor creature hung by a thread, Gautama stepped forward and cried, "Stop the cruel deed, O king!". And as he said this, he leaned forward and unfastened the bonds of the victim. "Every creature" he said, "loves to live, even as every human being loves to preserve his or her life". The priest then threw the knife away like a repentant sinner and the king issued a royal decree throughout the land the next day, to the effect that no further sacrifice should be made in future and that all people should show mercy to birds and beasts alike.

Kisagotami, a young woman, was married to the only son of a rich man and they had a male child. The child died when he was two years old. Kisagotami had intense attachment for the child. She clasped the dead child to her bossom, refused to part with it, and went from house to house, to her friends and relatives, asking them to give some medicine to bring the child back to life. A Buddhist monk said to her: "O good girl! I have no medicine. But go to Lord Buddha. He can surely give you a very good medicine. He is an ocean of mercy and love. The child will come back to life. Be not troubled". She at once ran to Buddha and said, "O venerable sir! Can you give any medicine to this child ?". Buddha replied, "Yes. I will give you a very good medicine. Bring some mustard seed from some house where no child or husband or wife or father or mother or servant had died". She said, "Very good, sir, I shall bring it in a short time".

Carrying her dead child in her bossom, Kisagotami went to a house and asked for some mustard seed. The people of the house said, "O lady, here is mustard seed. Take it". Kisagotami asked, "In your house, has any son or husband or wife, father or mother or servant died ?". They replied, "O lady! You ask a very strange question. Many have died in our house". Kisagotami went to another house and asked the same. The owner of the house said, "I have lost my eldest son and my wife". She went to a third house. People of the house answered, "We have lost our parents". She went to another house. The lady of the house said, "I lost my husband last year". Ultimately Kisagotami was not able to find a single house where no one had died. Viveka and Vairagya dawned in her mind. She buried the dead body of her child. She began to reflect seriously on the problem of life and death in this world.

Kisagotami then went to Lord Buddha and prostrated at his lotus feet. Buddha said to her, "O good girl! Have you brought the mustard seed ?". Kisagotami answered, "I am not able to find a single house where no one has died". Then Buddha said, "All the objects of this world are perishable and impermanent. This world is full of miseries, troubles and tribulations. Man or woman is troubled by birth, death, disease, old age and pain. We should gain wisdom from experience. We should not expect for things that do not and will not happen. This expectation leads us to unnecessary misery and suffering. One should obtain Nirvana. Then only all sorrows will come to an end. One will attain immortality and eternal peace". Kisagotami then became a disciple of Buddha and entered the Order of Nuns.

Once Buddha went to the house of a rich Brahmin with bowl in hand. The Brahmin became very angry and said, "O Bhikshu, why do you lead an idle life of wandering and begging ? Is this not disgraceful ? You have a well-built body. You can work. I plough and sow. I work in the fields and I earn my bread at the sweat of my brow. I lead a laborious life. It would be better if you also plough and sow and then you will have plenty of food to eat". Buddha replied, "O Brahmin! I also plough and sow, and having ploughed and sown, I eat". The Brahmin said, "You say you are an agriculturist. I do not see any sign of it. Where are your plough, bullocks and seeds ?". Then Buddha replied, "O Brahmin! Just hear my words with attention. I sow the seed of faith. The good actions that I perform are the rain that waters the seeds. Viveka and Vairagya are parts of my plough. Righteousness is the handle. Meditation is the goad. Sama and Dama - tranquillity of the mind and restraint of the Indriyas (senses) - are the bullocks. Thus I plough the soil of the mind and remove the weeds of doubt, delusion, fear, birth and death. The harvest that comes in is the immortal fruit of Nirvana. All sorrows terminate by this sort of ploughing and harvesting". The rich arrogant Brahmin came to his senses. His eyes were opened. He prostrated at the feet of Buddha and became his lay adherent.

Lord Buddha preached: "We will have to find out the cause of sorrow and the way to escape from it. The desire for sensual enjoyment and clinging to earthly life is the cause of sorrow. If we can eradicate desire, all sorrows and pains will come to an end. We will enjoy Nirvana or eternal peace. Those who follow the Noble Eightfold Path strictly, viz., right opinion, right resolve, right speech, right conduct, right employment, right exertion, right thought and right self-concentration will be free from sorrow. This indeed, O mendicants, is that middle course which the Tathagata has thoroughly comprehended, which produces insight, which produces knowledge, which leads to calmness or serenity, to supernatural knowledge, to perfect Buddhahood, to Nirvana.

"This again, indeed, O mendicants, is the noble truth of suffering. Birth is painful, old age is painful, sickness is painful, association with unloved objects is painful, separation from loved objects is painful, the desire which one does not obtain, this is too painful - in short, the five elements of attachment to existence are painful. The five elements of attachment to earthly existence are form, sensation, perception, components and consciousness.

"This again, indeed, O mendicants, is the truth of the cause of suffering. It is that thirst which leads to renewed existence, connected with joy and passion, finding joy here and there, namely, thirst for sensual pleasure, and the instinctive thirst for existence. This again, indeed, O mendicants, is the noble truth of cessation of suffering, which is the cessation and total absence of desire for that very thirst, its abandonment, surrender, release from it and non-attachment to it. This again, indeed, O mendicants, is the noble truth of the course which leads to the cessation of suffering. This is verily the Noble Eightfold Path, viz., right opinion, etc."

|

|

Buddhism is a religion indigenous to the Indian subcontinent that encompasses a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, who is commonly known as the Buddha, meaning "the awakened one". The Buddha lived and taught in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent sometime between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[1] He is recognized by Buddhists as an awakened or enlightened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end their suffering (dukkha) through the elimination of ignorance (avidy) by way of understanding and the seeing of dependent origination (prattyasamutpda) and the elimination of desire (tah), and thus the attainment of the cessation of all suffering, known as the sublime state of nirva.[2] |

Two major branches of Buddhism are generally recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar etc.). Mahayana is found throughout East Asia (China, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Singapore, Taiwan etc.) and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, and Tiantai (Tendai). In some classifications, Vajrayana"practiced mainly in Tibet and Mongolia, and adjacent parts of China and Russia"is recognized as a third branch, while others classify it as a part of Mahayana.

While Buddhism remains most popular within Asia and India, both branches are now found throughout the world. Estimates of Buddhists worldwide vary significantly depending on the way Buddhist adherence is defined. Estimates range from 350 million to 1.6 billion, with 350-550 million the most widely accepted figure. Buddhism is also recognized as one of the fastest growing religions in the world.[3][4][5][6]

Buddhist schools vary on the exact nature of the path to liberation, the importance and canonicity of various teachings and scriptures, and especially their respective practices.[7] The foundations of Buddhist tradition and practice are the Three Jewels: the Buddha, the Dharma (the teachings), and the Sangha (the community). Taking "refuge in the triple gem" has traditionally been a declaration and commitment to being on the Buddhist path, and in general distinguishes a Buddhist from a non-Buddhist.[8] Other practices may include following ethical precepts; support of the monastic community; renouncing conventional living and becoming a monastic; the development of mindfulness and practice of meditation; cultivation of higher wisdom and discernment; study of scriptures; devotional practices; ceremonies; and in the Mahayana tradition, invocation of buddhas and bodhisattvas.

This narrative draws on the Nidnakath biography of the Theravda sect in Sri Lanka, which is ascribed to Buddhaghoa in the 5th century CE.[9] Earlier biographies such as the Buddhacarita, the Lokottaravdin Mahvastu, and the Mahyna / Sarvstivda Lalitavistara Stra, give different accounts. Scholars are hesitant to make unqualified claims about the historical facts of the Buddha's life. Most accept that he lived, taught and founded a monastic order, but do not consistently accept all of the details contained in his biographies.[10][11]

According to author Michael Carrithers, while there are good reasons to doubt the traditional account, "the outline of the life must be true: birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death."[12] In writing her biography of the Buddha, Karen Armstrong noted, "It is obviously difficult, therefore, to write a biography of the Buddha that meets modern criteria, because we have very little information that can be considered historically sound... [but] we can be reasonably confident Siddhatta Gotama did indeed exist and that his disciples preserved the memory of his life and teachings as well as they could."[13][dubious - discuss]

The evidence of the early texts suggests that Siddhrtha Gautama was born in a community that was on the periphery, both geographically and culturally, of the northeastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE.[14] It was either a small republic, in which case his father was an elected chieftain, or an oligarchy, in which case his father was an oligarch.[14]

According to the Theravada Tripitaka scriptures[which?] (from Pali, meaning "three baskets"), Gautama was born in Lumbini in modern-day Nepal, around the year 563 BCE, and raised in Kapilavastu.[15][16]

According to this narrative, shortly after the birth of young prince Gautama, an astrologer named Asita visited the young prince's father"King uddhodana"and prophesied that Siddhartha would either become a great king or renounce the material world to become a holy man, depending on whether he saw what life was like outside the palace walls.

uddhodana was determined to see his son become a king, so he prevented him from leaving the palace grounds. But at age 29, despite his father's efforts, Gautama ventured beyond the palace several times. In a series of encounters"known in Buddhist literature as the four sights"he learned of the suffering of ordinary people, encountering an old man, a sick man, a corpse and, finally, an ascetic holy man, apparently content and at peace with the world. These experiences prompted Gautama to abandon royal life and take up a spiritual quest.

Gautama first went to study with famous religious teachers of the day, and mastered the meditative attainments they taught. But he found that they did not provide a permanent end to suffering, so he continued his quest. He next attempted an extreme asceticism, which was a religious pursuit common among the Shramanas, a religious culture distinct from the Vedic one. Gautama underwent prolonged fasting, breath-holding, and exposure to pain. He almost starved himself to death in the process. He realized that he had taken this kind of practice to its limit, and had not put an end to suffering. So in a pivotal moment he accepted milk and rice from a village girl and changed his approach. He devoted himself to anapanasati meditation, through which he discovered what Buddhists call the Middle Way (Skt. madhyam-pratipad[17]): a path of moderation between the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification.[18][19]

Gautama was now determined to complete his spiritual quest. At the age of 35, he famously sat in meditation under a sacred fig tree " known as the Bodhi tree " in the town of Bodh Gaya, India, and vowed not to rise before achieving enlightenment. After many days, he finally destroyed the fetters of his mind, thereby liberating himself from the cycle of suffering and rebirth, and arose as a fully enlightened being (Skt. samyaksabuddha). Soon thereafter, he attracted a band of followers and instituted a monastic order. Now, as the Buddha, he spent the rest of his life teaching the path of awakening he had discovered, traveling throughout the northeastern part of the Indian subcontinent,[20][21] and died at the age of 80 (483 BCE) in Kushinagar, India. The south branch of the original fig tree available only in Anuradhapura Sri Lanka is known as Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi.

Within Buddhism, samsara is defined as the continual repetitive cycle of birth and death that arises from ordinary beings' grasping and fixating on a self and experiences. Specifically, samsara refers to the process of cycling through one rebirth after another within the six realms of existence,[a] where each realm can be understood as physical realm or a psychological state characterized by a particular type of suffering. Samsara arises out of avidya (ignorance) and is characterized by dukkha (suffering, anxiety, dissatisfaction). In the Buddhist view, liberation from samsara is possible by following the Buddhist path.[b]

In Buddhism, Karma (from Sanskrit: "action, work") is the force that drives sasra"the cycle of suffering and rebirth for each being. Good, skillful deeds (Pli: "kusala") and bad, unskillful (Pli: "akusala") actions produce "seeds" in the mind that come to fruition either in this life or in a subsequent rebirth.[22] The avoidance of unwholesome actions and the cultivation of positive actions is called la (from Sanskrit: "ethical conduct").

In Buddhism, karma specifically refers to those actions of body, speech or mind that spring from mental intent ("cetana"),[23] and bring about a consequence or fruit, (phala) or result (vipka).

In Theravada Buddhism there can be no divine salvation or forgiveness for one's karma, since it is a purely impersonal process that is a part of the makeup of the universe. In Mahayana Buddhism, the texts of certain Mahayana sutras (such as the Lotus Sutra, the Angulimaliya Sutra and the Nirvana Sutra) claim that the recitation or merely the hearing of their texts can expunge great swathes of negative karma. Some forms of Buddhism (for example, Vajrayana) regard the recitation of mantras as a means for cutting off of previous negative karma.[24] The Japanese Pure Land teacher Genshin taught that Amida Buddha has the power to destroy the karma that would otherwise bind one in sasra.[25][26]

Rebirth refers to a process whereby beings go through a succession of lifetimes as one of many possible forms of sentient life, each running from conception[27] to death. Buddhism rejects the concepts of a permanent self or an unchanging, eternal soul, as it is called in Hinduism and Christianity. According to Buddhism there ultimately is no such thing as a self independent from the rest of the universe (the doctrine of anatta). Buddhists also refer to themselves as the believers of the anatta doctrine"Nairatmyavadin or Anattavadin. Rebirth in subsequent existences must be understood as the continuation of a dynamic, ever-changing process of "dependent arising" ("prattyasamutpda") determined by the laws of cause and effect (karma) rather than that of one being, transmigrating or incarnating from one existence to the next.

Each rebirth takes place within one of five realms according to Theravadins, or six according to other schools.[28][29]

The above are further subdivided into 31 planes of existence.[32] Rebirths in some of the higher heavens, known as the uddhvsa Worlds or Pure Abodes, can be attained only by skilled Buddhist practitioners known as angmis (non-returners). Rebirths in the arupa-dhatu (formless realms) can be attained by only those who can meditate on the arpajhnas, the highest object of meditation.

According to East Asian and Tibetan Buddhism, there is an intermediate state (Tibetan "Bardo") between one life and the next. The orthodox Theravada position rejects this; however there are passages in the Samyutta Nikaya of the Pali Canon (the collection of texts on which the Theravada tradition is based), that seem to lend support to the idea that the Buddha taught of an intermediate stage between one life and the next.[33][34]

The teachings on the Four Noble Truths are regarded as central to the teachings of Buddhism, and are said to provide a conceptual framework for Buddhist thought. These four truths explain the nature of dukkha (suffering, anxiety, dissatisfaction), its causes, and how it can be overcome. The four truths are:[c]

The first truth explains the nature of dukkha. Dukkha is commonly translated as "suffering", "anxiety", "dissatisfaction", "unease", etc., and it is said to have the following three aspects:

The second truth is that the origin of dukkha can be known. Within the context of the four noble truths, the origin of dukkha is commonly explained as craving (Pali: tanha) conditioned by ignorance (Pali: avijja). On a deeper level, the root cause of dukkha is identified as ignorance (Pali: avijja) of the true nature of things. The third noble truth is that the complete cessation of dukkha is possible, and the fourth noble truth identifies a path to this cessation.[c]

The Noble Eightfold Path"the fourth of the Buddha's Noble Truths"consists of a set of eight interconnected factors or conditions, that when developed together, lead to the cessation of dukkha.[35] These eight factors are: Right View (or Right Understanding), Right Intention (or Right Thought), Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

Ajahn Sucitto describes the path as "a mandala of interconnected factors that support and moderate each other."[35] The eight factors of the path are not to be understood as stages, in which each stage is completed before moving on to the next. Rather, they are understood as eight significant dimensions of one's behaviour"mental, spoken, and bodily"that operate in dependence on one another; taken together, they define a complete path, or way of living.[36]

The eight factors of the path are commonly presented within three divisions (or higher trainings) as shown below:

| Division | Eightfold factor | Sanskrit, Pali | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wisdom (Sanskrit: praj, Pli: pa) |

1. Right view | samyag di, samm ditthi |

Viewing reality as it is, not just as it appears to be |

| 2. Right intention | samyag sakalpa, samm sankappa |

Intention of renunciation, freedom and harmlessness | |

| Ethical conduct (Sanskrit: la, Pli: sla) |

3. Right speech | samyag vc, samm vca |

Speaking in a truthful and non-hurtful way |

| 4. Right action | samyag karman, samm kammanta |

Acting in a non-harmful way | |

| 5. Right livelihood | samyag jvana, samm jva |

A non-harmful livelihood | |

| Concentration (Sanskrit and Pli: samdhi) |

6. Right effort | samyag vyyma, samm vyma |

Making an effort to improve |

| 7. Right mindfulness | samyag smti, samm sati |

Awareness to see things for what they are with clear consciousness; being aware of the present reality within oneself, without any craving or aversion |

|

| 8. Right concentration | samyag samdhi, samm samdhi |

Correct meditation or concentration, explained as the first four jhnas |

While he searched for enlightenment, Gautama combined the yoga practice of his teacher Kalama with what later became known as "the immeasurables".[37][dubious - discuss] Gautama thus invented a new kind of human, one without egotism.[37][dubious - discuss] What Thich Nhat Hanh calls the "Four Immeasurable Minds" of love, compassion, joy, and equanimity[38] are also known as brahmaviharas, divine abodes, or simply as four immeasurables.[39] Pema Chdrn calls them the "four limitless ones".[40] Of the four, mett or loving-kindness meditation is perhaps the best known.[39] The Four Immeasurables are taught as a form of meditation that cultivates "wholesome attitudes towards all sentient beings."[41] The practitioner prays:

An important guiding principle of Buddhist practice is the Middle Way (or Middle Path), which is said to have been discovered by Gautama Buddha prior to his enlightenment. The Middle Way has several definitions:

Buddhist scholars have produced a remarkable quantity of intellectual theories, philosophies and world view concepts (see, for example, Abhidharma, Buddhist philosophy and Reality in Buddhism). Some schools of Buddhism discourage doctrinal study, and some regard it as essential practice.

The concept of liberation (nirva)"the goal of the Buddhist path"is closely related to overcoming ignorance (avidy), a fundamental misunderstanding or mis-perception of the nature of reality. In awakening to the true nature of the self and all phenomena one develops dispassion for the objects of clinging, and is liberated from suffering (dukkha) and the cycle of incessant rebirths (sasra). To this end, the Buddha recommended viewing things as characterized by the three marks of existence.

The Three Marks of Existence are impermanence, suffering, and not-self.

Impermanence (Pli: anicca) expresses the Buddhist notion that all compounded or conditioned phenomena (all things and experiences) are inconstant, unsteady, and impermanent. Everything we can experience through our senses is made up of parts, and its existence is dependent on external conditions. Everything is in constant flux, and so conditions and the thing itself are constantly changing. Things are constantly coming into being, and ceasing to be. Since nothing lasts, there is no inherent or fixed nature to any object or experience. According to the doctrine of impermanence, life embodies this flux in the aging process, the cycle of rebirth (sasra), and in any experience of loss. The doctrine asserts that because things are impermanent, attachment to them is futile and leads to suffering (dukkha).

Suffering (Pli: - dukkha; Sanskrit - dukha) is also a central concept in Buddhism. The word roughly corresponds to a number of terms in English including suffering, pain, unsatisfactoriness, sorrow, affliction, anxiety, dissatisfaction, discomfort, anguish, stress, misery, and frustration. Although the term is often translated as "suffering", its philosophical meaning is more analogous to "disquietude" as in the condition of being disturbed. As such, "suffering" is too narrow a translation with "negative emotional connotations"[44] that can give the impression that the Buddhist view is pessimistic, but Buddhism seeks to be neither pessimistic nor optimistic, but realistic. In English-language Buddhist literature translated from Pli, "dukkha" is often left untranslated, so as to encompass its full range of meaning.[45][46][47]

Not-self (Pli: anatta; Sanskrit: antman) is the third mark of existence. Upon careful examination, one finds that no phenomenon is really "I" or "mine"; these concepts are in fact constructed by the mind. In the Nikayas anatta is not meant as a metaphysical assertion, but as an approach for gaining release from suffering. In fact, the Buddha rejected both of the metaphysical assertions "I have a Self" and "I have no Self" as ontological views that bind one to suffering.[48] When asked if the self was identical with the body, the Buddha refused to answer. By analyzing the constantly changing physical and mental constituents (skandhas) of a person or object, the practitioner comes to the conclusion that neither the respective parts nor the person as a whole comprise a self.

The doctrine of prattyasamutpda (Sanskrit; Pali: paticcasamuppda; Tibetan: rten.cing.'brel.bar.'byung.ba; Chinese: ) is an important part of Buddhist metaphysics. It states that phenomena arise together in a mutually interdependent web of cause and effect. It is variously rendered into English as "dependent origination", "conditioned genesis", "dependent co-arising", "interdependent arising", or "contingency".

The best-known application of the concept of prattyasamutpda is the scheme of Twelve Nidnas (from Pli "nidna" meaning "cause, foundation, source or origin"), which explain the continuation of the cycle of suffering and rebirth (sasra) in detail.[49]

The Twelve Nidnas describe a causal connection between the subsequent characteristics or conditions of cyclic existence, each one giving rise to the next:

Sentient beings always suffer throughout sasra, until they free themselves from this suffering by attaining Nirvana. Then the absence of the first Nidana"ignorance"leads to the absence of the others.

Edited by RoseFairy - 10 years agoMahayana Buddhism received significant theoretical grounding from Nagarjuna (perhaps c. 150-250 CE), arguably the most influential scholar within the Mahayana tradition. Nagarjuna's primary contribution to Buddhist philosophy was the systematic exposition of the concept of nyat, or "emptiness", widely attested in the Prajpramit sutras that emerged in his era. The concept of emptiness brings together other key Buddhist doctrines, particularly anatta and prattyasamutpda (dependent origination), to refute the metaphysics of Sarvastivada and Sautrantika (extinct non-Mahayana schools). For Nagarjuna, it is not merely sentient beings that are empty of tman; all phenomena (dharmas) are without any svabhava (literally "own-nature" or "self-nature"), and thus without any underlying essence; they are "empty" of being independent; thus the heterodox theories of svabhava circulating at the time were refuted on the basis of the doctrines of early Buddhism. Nagarjuna's school of thought is known as the Mdhyamaka. Some of the writings attributed to Nagarjuna made explicit references to Mahayana texts, but his philosophy was argued within the parameters set out by the agamas. He may have arrived at his positions from a desire to achieve a consistent exegesis of the Buddha's doctrine as recorded in the Canon. In the eyes of Nagarjuna the Buddha was not merely a forerunner, but the very founder of the Mdhyamaka system.[55]