Article from guardian newspaper UK

Rabindranath Tagore was a global phenomenon, so why is he neglected?

Is his poetry any good? The answer for anyone who can't read Bengali must be: don't know. No translation is up to the job

-

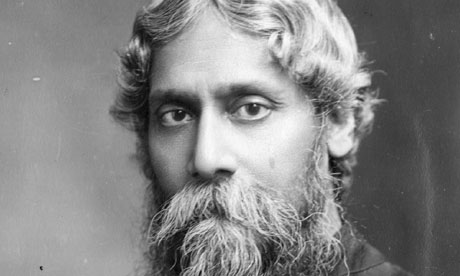

Rabindranath Tagore became the embodiment of how the west wanted to see the east. Photograph: Hulton Archive

Rabindranath Tagore was born 150 years ago today. This weekend

festivities and seminars are being held in his honour across the world.

In London, the BFI is hosting a season of films inspired by his work;

last night his fellow Bengali (and fellow Nobel laureate) Amartya Sen

gave a talk at the British Museum; a two-day conference at the

University of London will, among other things, examine his legacy in the

Netherlands, Poland and Germany.

I consulted two dictionaries of

quotations, the Oxford and Penguin, to check the most memorable lines of

this poet, novelist, essayist, song and short story writer. Not a

single entry. They skipped from Tacitus to Hippolyte Taine as if there

was nothing in Tagore's collected works (28 thick books, even with his

2,500 songs published separately) that ever had stuck in anyone's mind,

or was so pithily expressed that it deserved to; as if what had come out

of Tagore's pen was a kind of oriental ectoplasm, floating high above

our materialist western heads, and ungraspable. In fact, I could

remember one line clearly enough, and vaguely remember a whole stanza.

The first is how he described the Taj Mahal: like "a teardrop on the

face of eternity". The second is the inscription Wilfred Owen's mother

found in her dead son's pocketbook: "When I go from hence, let this be

my parting word, that what I have seen is unsurpassable." But I owe this

knowledge to (a) a tourist guide in Agra, and (b) to a biography.

Reading Tagore himself had nothing to do with it.

True, writers

can't be ranked merely by their quotability, but Tagore's neglect is

extraordinary. No other language group reveres a writer as 250 million

Bengali-speakers do Tagore. Shakespeare and Dickens don't come into

the picture; the popularity of Burns in Scotland 100 years ago may be

his nearest equivalent in Britain. Every Bengali will know some Tagore,

even if they can't read or write and the words come from a popular song

or the national anthem (those of both India and Bangladesh use his

verse). The visitor to Bengal can easily find some comedy in the mass

adoration. Years ago, trying to penetrate a layer of Kolkata

bureaucracy, I spent hours listening to bureaucrats on the subject of

Tagore – "his translations into English are like embroidery seen from

the back," one said – while getting nowhere with the unrelated topic I

was meant to be investigating. Then again, love of literature can slide

into fetishism, and from there, obscenity. When Tagore died in 1941, the

huge crowd around his funeral cortege plucked hairs from his head. At

the cremation pyre, mourners burst through the cordon before the body

had been completely consumed by fire, searching for bones and keepsakes.

It's

hard to think of any other writer anywhere who has aroused this level

of fervour, but Tagore might still be seen as a purely local phenomenon,

a curiosity and irrelevance to the world beyond Bengal. Except that he

wasn't. In 1913 he won the Nobel prize for literature,

the first non-European to win a Nobel. The story is well known. In 1912

he sailed from India to England with a collection of English

translations – the 100 or so poems that became the anthology Gitanjali,

or "song offerings". He lost the manuscript on the London tube.

Famously, it was found in a left luggage office. Then – decisively – WB

Yeats met Tagore, read his poems and became his passionate advocate

(while pencilling in suggestions for improvements).

Events moved

at breathtaking speed. Tagore had arrived in London in June, he had his

anthology published by Macmillan with an introduction by Yeats in the

following March, and on 13 November 1913 he was awarded the Nobel.

Before he left Kolkata he knew one person in London, the painter William

Rothenstein. Two years later he was a global phenomenon. The notion

that literary prizes secure reputations and sell books is modern

publishing wisdom, but nothing compares with what the Nobel did for

Tagore a century ago. Gitanjali found a vast audience in its many

editions. In the tremulous months before the first world war, as well as

during the war, its spiritual message and reverence for the natural

world struck a chord. It contains the lines Owen wrote in his

pocketbook, and soon had translations in many other languages, including

French, by Andr Gide, and Russian, by Boris Pasternak.

The

success turned everyone's heads, including Tagore's. He became the most

prominent embodiment of how the west wanted to see the east – sagelike,

mystical, descending from some less developed but perhaps more innocent

civilisation; above all, exotic. He looked the part, with his white

robes and flowing beard and hair, and sometimes overplayed it. Of

course, the truth was more complicated. The Tagores were among Kolkata's

most influential families. They'd prospered in their role as middle men

to the East India Company, whose servants named them Tagore because it

was more easily pronounced than the Bengali title, Thakur. The west

wasn't strange to them. Rabindranath's grandfather, Dwarkanath, owned

steam tug companies and coal mines, became a favourite of Queen

Victoria's and died in England (his tombstone is in Kensal Green

cemetery). As for the poet himself, this was his third visit to London.

On his first, he'd heard the music hall songs and folk tunes that he

later incorporated into his distinctive musical genre, rabindra sangeet.

More

than anything, what Tagore stood for was a synthesis of east and west.

He admired the European intellect and felt betrayed when Britain's

conduct in India let down the ideal. His western enthusiasts, however,

saw what they wanted to see. First, he was an exotic fashion and then he

was not. "Damn Tagore," wrote Yeats in 1935, blaming the "sentimental

rubbish" of his later books for ruining his reputation. "An Indian has

written to ask what I think of Rabindrum [sic] Tagore," wrote Philip

Larkin to his friend Robert Conquest in 1956. "Feel like sending him a

telegram: 'f**k all. Larkin.'"

Is his poetry

any good? The answer for anyone who can't read Bengali must be: don't

know. No translation (according to Bengalis) lives up to the job, and at

their worst, they can read like In Memoriam notices: "Faith is the bird

that feels the light when the dawn is still dark" is among the better

lines. Translator William Radice thinks that Tagore's willingness to

tackle the big questions, heart on sleeve, has made him vulnerable to

"philistinism or contempt". That may be so – see Larkin – but perhaps

the time has come for us to forget Tagore was ever a poet, and think of

his more intelligible achievements. These are many. He was a fine

essayist; an educationist who founded a university; an opponent of the

terrorism that then plagued Bengal; a secularist amid religious

divisions; an agricultural improver and ecologist; a critical

nationalist. In his fiction,

he showed an understanding of women – their discontents and dilemmas in

a patriarchal society – that was ahead of its time. On his 150th

anniversary, we shouldn't resist two cheers, at least.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/may/07/rabindranath-tagore-why-was-he-neglected

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Economic times...

A tribute to Rabindranath Tagore: Nation to celebrate his 150th birth anniversary

May 6, 2011, 01.15am IST

"Creation is not repetition, or correspondence in every particular

between the object and its artistic presentation. The world of reality

is all around us. When I look at this phenomenon with my artist's eye,

things are revealed in a different light which I try and recapture in my

picture - call them realistic or not. There is a world of dreams and

fantasies which exists only in a man's imagination. If I can but depict

this in my pictures I can beat the Creator at His own game."

--

Rabindranath TagoreIn 1916 he was known as The King of the Dark Chamber, in a Macmillan

hardcover that had a frontispiece portrait by famed friend William

Rothenstein. Now nearly a century away on 8 May at the

NGMA in

Delhi, when the nation will celebrates Tagore's 150 birth centenary, curator

Ela Dutt

dips into the NGMA collection and comes up with a tribute to Tagore.

Art lovers can rejoice, for here are the three Tagores - Rabindranath,

Abanindranath and

Gagendranath.

The world that Rabindranath revealed in his works was one of

self-reflexive evolution, where the images themselves were in the

process of taking shape, as was his art. Gagendranath's works brim with

romance and Abanindranath's pice de rsistance is Meeting at the

Staircase.

Rabindranath Tagore's paintings were

displayed publicly for the first time in Paris in 1930, followed by an

exhibition in Calcutta in 1931. At about the same time he began to

create portraits. By about 1932 Tagore became interested in

self-portraits and it is believed that a number of works in this suite

date from about this period. As with many of his other self-portraits,

the Study in Face has a prophet-like serenity mixed with a sense of

inner anguish.

"People often ask me about the meaning

of my pictures. I remain silent even as my pictures are. It is for them

to express and not to explain," Rabindranath Tagore said once. His early

paintings were rendered in monochromatic schemes, followed by two-toned

and three-toned drawings. Other than a pen the artist used his fingers,

bits of cotton wool and rag to daub, smudge and rub the inks to create

color tones of great depth and intensity. In many of his head studies as

well as the Dancing Lady studies, there is an underlying sense of

mysticism that has a mesmeric appeal.

Rabindranath's

heads and figures executed in a variety of styles have elicited the most

interest. Restrained yet restless, suggestive, bizarre and haunting,

these portraits are considered to be among his most memorable works.

"The pensive ovoid face of a woman with large unwavering, soulful eyes

was perhaps his most obsessive theme. Exhibited first in 1930, endless

variations of the same mood-image continued to emerge throughout. The

earlier ones were delicately modelled and opalescent, while the later

examples were excessively dramatic with intensely lit forehead,

exaggerated nose-ridge, painted in strong colours, bodied forth from a

primal gloom." (Robinson, The Art of Rabindranath Tagore, Calcutta,

1989)

There are a number of images that recall the

linguistic ardour of Rabindranath. Interestingly, the poet and

playwright began painting late in life as he was nearing 70. In a letter

from 1928 to Rani Mahalanobis he says: "The most important item in the

bulletin of my daily news, is my painting. I am hopelessly entangled in

the spell that the lines have cast all around me... I have almost

managed to forget that there used to be a time when I wrote poetry.

The subject matter of a poem can be traced back to some dim thought in

the mind...while painting, the process adopted by me is quite the

reverse. First, there is the hint of a line, then the line becomes a

form...this creation of form is an endless wonder. If I were a finished

artist, I probably would have followed a preconceived idea in making a

picture...but it is far more exciting when the mind is seized by

something outside of it, some compulsive surprise element gradually

assuming an understandable form."

At the NGMA, this

cachet of charismatic works will evince both interest and intrigue.

Heads and landscapes abound in this collection. It is a flashback to the

yesteryears, when the pace of life flowed like a river. There are a few

landscapes, which seem a direct translation of the breathtaking

Calcutta sunset. Rabindranath's words are emblematic. "I believe that

the vision of paradise is to be seen in the sunlight and the green of

the earth, in the beauty of the human face and the wealth of human life,

even in objects that are seemingly insignificant and unprepossessing."

This curation by Ela Dutt signifies the moot point of the act of

creation. It also leaves something to savour in the common thread that

runs through it. In more ways than one it configures Anand

Coomaraswamy's intention: "The artist, like a child, invents his own

techniques as he goes along; nothing has been allowed to interfere with

zest. The means are always adequate to the end in view: this end is not

'Art' with a capital A, on the one hand - nor, on the other, a merely

pathological self-expression; not art intended to improve our minds, nor

to provide for the artist himself an 'escape'; but without ulterior

motives, truly innocent, like the creation of a universe."

What intrigues even more is the fact that Rabindranath had once written

an article entitled 'My Pictures' in which he wrote: "The Universe ...

talks in the voice of pictures and dance...In a picture the artist

creates the language of undoubted reality, and we are satisfied that we

see. It may not be the representation of a beautiful woman but that of a

commonplace donkey or of something that has no external credential of

truth in nature but only in its own inner artistic significance."

The paper works are a sight to behold. Rabindranath is known to have

scribbled lines of poetry on the reverse of a paper work too. Last year

at Sotheby's a work had the inscription which read: "I saw in front of

me the vast field/of work extending to the horizon,/therein lies my

great freedom./In the evening I came and sat on/my balcony, The cage has

been/broken. The split chain still clings/onto the bird's leg. Movement

will/make it jingle."

This show echoes the vitality of

freedom, the mood of inspiration and the idea of artistic control being

equal and complimentary in the measures of artistic ferment. It also

reaffirms the truth that the role of a museum is not merely to collect

and stock art like stacks, but to encourage, and develop the study of

the fine arts, so as to nurture the application of arts to practical

life, to advance the general knowledge of kindred subjects, to furnish

popular and intellectual instruction in the service of society. You

could walk around this elegant Circle of Three Tagores and mull over the

poet Laureate's words: "The night is black/ Kindle the lamp of love/

With thy life and devotion."

@red-Did the nation REALLY celebrate??or atleast remembered him?? :@